Finding Their Way

JACSW Policy Center Helping Formerly Incarcerated Move Toward a New Life

Opening Paragraphs Heading link

The kitchen, living room, bedrooms, and bathroom at the suburban Chicago apartment of Demond Weston McIntosh may seem small to some, but it is enormous compared to where he lived for nearly 30 years.

Dixon Correctional Center was McIntosh’s home from the age of 17 to 47, spending his formative years confined to a concrete cell for a crime he did not commit. Since his release on Dec. 19, 2019, McIntosh has not only been piecing his life back together, but helping others who were imprisoned like him do the same. Guiding him along the way has been the Jane Addams Center for Social Policy and Research.

Since its inception, the Policy Center has conducted groundbreaking research on the impact of incarceration on families, hosting seminars and convening follow-up discussions with state agencies, among other activities. Led by Policy Center Strategic Initiatives Director John Holton, PhD, University of Illinois Chicago Jane Addams College of Social Work Dean Creasie Finney Hairston, PhD, and Policy Center Associate Director Joe Strickland, PhD, a grant was secured from the Illinois Department on Aging (IDOA) to develop a strategic plan to assist marginalized groups (such as older individuals who had been formerly incarcerated) in offering support to overcome adversity and lead a fulfilled life.

More than 53,000 Illinois residents are confined in prisons, jails, immigration detention centers, and juvenile facilities. According to the Prison Policy Initiative, a non-profit, nonpartisan organization that conducts research to expose the broader harm of mass criminalization that then sparks advocacy campaigns, Illinois has an incarceration rate of 497 per 100,000 people. Black individuals are being jailed 7.5 times higher than whites. In the 30 years from 1991 to 2021, the percentage of state and federal prison population nationwide aged 55 or older rose from 3% to 15%.

The cost of incarcerating older people is expensive and their risk of reincarceration is low, yet 12% of people in Illinois prisons are over the age of 55. In Illinois, Black males comprise 7% of the state’s population, but 54% of its incarcerated population.

“The likelihood that African American males constitute the larger share of older inmates who become eligible to transition to society is noteworthy,” Holton said. “Returning residents will have more stigma and bias from the communities that receive them, as they are already taxed with unemployment, overcrowding, disinvestment, and crime. These “returning citizens” will need assistance from the Illinois Department of Aging, which differs from other marginalized groups.”

A focus group conducted by Holton and John Hardy, senior research specialist at the Policy Center, provided insight on how older individuals who were formerly incarcerated are learning to adapt to “normal” life activities and challenges – employment, relationships, paying bills, and creating new personal networks such as actively participating in faith-based institutions.

Individuals were asked about “aging in place,” a term defined by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention as “the ability to live in one’s own home and community safely, independently, and comfortably, regardless of age, income, or ability level.” All respondents were concerned about it, one saying, “it was like being forced back to the same environment you left.”

Participants described efforts to leave behind their formerly incarcerated lived experiences with the new freedoms as decarcerated individuals. Two participants created advocacy initiatives, but many discovered their efforts to resume everyday life are hindered by financial security, relationships, accessibility to services, and limited networks, Holton said. Affordable housing is a roadblock for many former prisoners.

“Some said they were able to secure housing, but not in their name. Others said they were unable to obtain their own place and were relegated to sleeping on a couch,” Holton said. “Unless a family member provides housing, decarcerated individuals have limited options. Many found it difficult to obtain credit and remain employed. More than one said they were set up to fail. One individual said he was scared to be released from prison. He was arrested and incarcerated nine separate times.”

Policy Center photo Heading link

Connecting at the Policy Center

A monthly group session led by Hardy helps formerly incarcerated older individuals connect with others like them who are attempting to return to a life of normalcy. McIntosh was one of the first to attend, and in the more than four years since leaving Dixon Correctional Center he has obtained a job and apartment. The past, however, is sometimes difficult to leave behind.

The year 1990 is still ingrained in his memory. The then 17-year-old was a high school student living with his mother, grandmother and three sisters in Englewood, a southside Chicago area rife with gang violence. Several shootings leading to one death and numerous injuries occurred over the course of several days in May due to disputes between rival gangs.

Nearly two weeks after the May 29 killing, McIntosh, who had never been involved in gang activity, was walking in his neighborhood when he was arrested. Police were reportedly searching for a suspect who was 5’8” tall, weighed 145 pounds, had black hair, brown eyes and a medium brown complexion – all the physical characteristics McIntosh possessed.

After hours of grueling interrogation at the police station, McIntosh was physically and mentally exhausted and confessed to the murder. During his April 1992 trial, he testified he was coerced to confess, as police withheld bathroom privileges and food, and McIntosh said he was repeatedly beaten. The police, however, refuted his testimony. It took jurors less than five hours to declare McIntosh guilty. A month after the trial he was sentenced to consecutive 45- and 30-year prison sentences – 75 years total.

McIntosh began filing petitions to have his conviction overturned in the late 1990s. It was reported that the detectives who interrogated him were part of the police squad that worked under former commander Jon Burge, who was later found guilty of having “directly participated in or implicitly approved the torture” of at least 118 people in police custody to force false convictions.

While in prison, McIntosh worked tirelessly to get his conviction overturned. In 2007, a private investigator reviewed his case and concluded he was innocent. Seven years later another petition was filed renewing his claim of innocence. New evidence was brought before a judge, and in 2016 she ruled there was sufficient evidence to support his sworn statement. After nearly 30 years, his nightmare was over, and he was released from prison in 2019.

Today, McIntosh works as a peer reentry specialist and learning fellow at Chicago Torture Justice Center, an organization that seeks to address the traumas of police violence and institutionalized racism through access to healing and wellness services, trauma-informed resources, and community connection. McIntosh has enjoyed his freedom, but his transition outside of prison has been anything but smooth. He has experienced many highs, but just as many lows. While attending an event, he met John Hardy, and during their conversation they discussed a monthly meeting with formerly incarcerated older individuals (50 years and older) at the Policy Center.

“Whenever I have the opportunity to attend, I do,” McIntosh said. “I’m still struggling in a lot of areas, and it’s good that I hear other people’s journeys. I’ve made new friends and it’s great to bounce ideas off them.”

Focus group quote Heading link

One individual said he was scared to be released from prison. He was arrested and incarcerated nine times.

Story continues Heading link

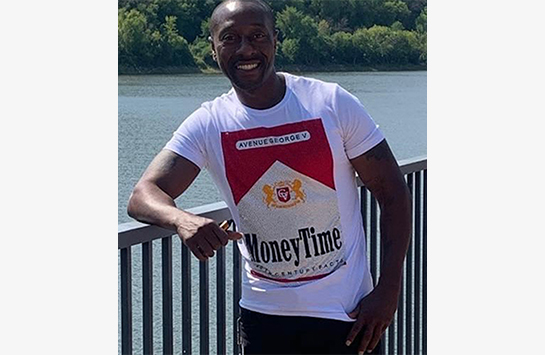

In 2019, the same year McIntosh was released, William Edwards (pictured at right), who like McIntosh often attends the monthly meetings, also walked out of prison a free man. Having been indicted in 1995 on drug conspiracy charges in federal court, Edwards was expecting to spend the rest of his life behind bars. Twenty-four years into his sentence, then President Donald Trump approved a bill that helped prisoners like himself seek release or reduce their sentence. Edwards waited 18 months before a judge officially granted his release.

The days behind bars are often tedious for prisoners, but Edwards was not going to allow his time go to waste. His days were filled with furthering his education, earning his General Equivalency Degree (GED) and spending hours in the library studying and researching materials to help gain his release. He also worked as a janitor, GED tutor/teacher, and cook. To reduce his stress, he exercised regularly.

Prior to his incarceration, Edwards’ family relied heavily on him,both financially and emotionally.

“Getting locked up damaged my family more than it did to me serving my sentence,” he said. “Since I’ve been out of prison, I’ve been listening to my family tell me how I damaged their lives at some point. I would tell people not to judge their family for not helping in the ways that we would expect coming home, because they may not be in position or could be holding bitterness about you being absent against your free will.”

Following his release, Edwards was reacquainted with several formerly incarcerated individuals he was housed with. Some were employed at Acclivus, an organization that supports community health and well-being for populations at-risk for violence and other negative health outcomes. His friends recommended Acclivus’ management team discuss a position with Edwards, and he was hired four years ago. Since then, he has been promoted twice and now supervises seven employees as a program manager.

“I have a passion for the work I do,” said Edwards, who lives in an apartment in Chicago’s Bronzeville neighborhood. “It’s very fulfilling to me.” The Policy Center, he said, has been an integral part of his success.

As the Policy Center’s senior research specialist, Hardy works night and day assisting individuals like Edwards and McIntosh reintegrate into society.

“I try to be available anytime I can,” he said. “I lend an ear to listen to what they are experiencing or provide a nudge to help push them forward in whatever their endeavor. I attempt to provide them with the resources they need to be successful so they can experience a smooth transition. In some cases it’s just a matter of a much-needed conversation and just knowing they have someone on their side or that has their best interest at heart, while trying to help.

“The formerly incarcerated have paid their debt to society, and the Policy Center wants them to have a fulfilling life outside of prison.”